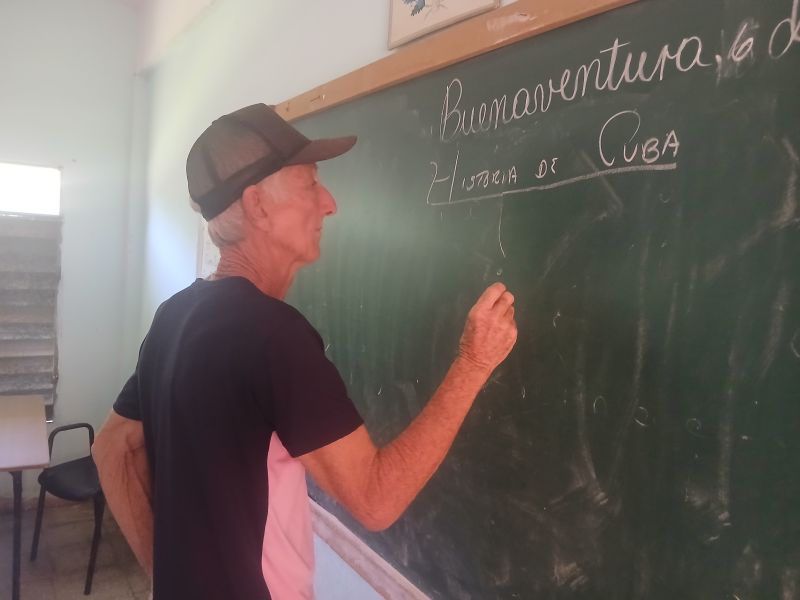

Cuban pedagogy owes its dedication, dedication, spirit of inquiry, and sense of belonging to History professor Gustavo Díaz García.

Cuban pedagogy owes its dedication, dedication, spirit of inquiry, and sense of belonging to History professor Gustavo Díaz García.

He tells me that he's been in the classroom for fifty-five years, "by vocation, and I had the privilege of starting to work with Subdilberto Camejo, a fiber educator, a glory of pedagogy in this municipality. We met at José Mercerón. There were two schools, one in Playa Manteca, Mayarí, and ours here in Holguín. Through study and work, we had the opportunity to become self-sufficient in milk, pork, poultry, and a farm planted with root vegetables, vegetables, and some grains. The only thing that wasn't produced was rice."

Meanwhile, Gustavo was training at the former Instituto de Superación (ISE) in the city of Holguín, which later became the Instituto de Perfeccionamiento Educacional (IPE), and graduated as a high school teacher. "I had the honor of being the first teacher in this municipality to work at Bartolomé Masó when the rural schools program called Plan San Andrés was inaugurated. There, at Masó, I worked for eight classes, and also at the Pedro Véliz Hernández Rural Secondary School. When the Municipal IPE was launched, I joined its team, even serving as head teacher for my specialty."

“At that institute, I had outstanding students, future teachers, among them the later journalism graduate Artemio Leyva Aguilera, Zoila Turruelles Ávila, Luis Ramón Reyes Moreno, who remains at the Rafael Cruz mixed-gender center, and another distinguished colleague in local history research, Danilo Guevara Bustamante. That is to say, my humble work contributed to the training of a generation of professionals who are key figures in the memory of this part of Holguín, and for that I feel happy.”

Díaz García is one of the professors who formed part of the first faculty of the Municipal University Center, and he still teaches. “After my retirement from adult education, I joined the university. I did so voluntarily for the first two years, and I have continued, now on staff, teaching history, philosophy, economics, methodology, didactics, and national security—in other words, various subjects assigned to us based on needs,” he expresses with satisfaction.

The rural schools were a founding force for him, where he trained and learned, but the teacher is saddened by the state of many of these centers due to the deterioration of their buildings. “I understand the economic situation the country is going through. They were exclusively for combining study and work, training them with responsibilities that are now scarce for these children. I also think that one primary boarding school that should have remained was the “Frank País García,” which was attended by children with financial difficulties.

I am almost at the end of my conversation with this prominent Calixteño educator and remind him that I understand that there is a continuity of the pedagogical heritage in the family. “My eldest daughter is a teacher and works at the Luis Saíz School in the Las Calabazas neighborhood where we live. She is a good professional and enjoys prestige. This excites me and tells me that I will retire from the classroom when my abilities no longer allow me to communicate fluently with my students. And that, I have told the calendar to please wait.”